Calculated change

Missourian Jeremy Zoglmann turns risk into reward for his commercial Angus herd.

By: Nicole Lane Erceg

It felt like an impossible scenario.

The sudden cancellation of a 20-year lease put commercial cattleman Jeremy Zoglmann on notice. He had to find a solution and find it fast.

“We had 200 cows and nowhere to go,” he recalls.

Affordable pasture inconceivable, herd dispersal out of the question, he was left scratching his head. Though the 325 Angus cows compete for Zoglmann’s time as he farms 6,000 acres in tandem with his father and brother, he wasn’t letting years of investment in the cattle business dissipate.

His solution? What you can’t buy, build.

He erected a 50 x 480-foot hoop barn just around the corner from his family’s Milo, Mo., home. Keeping a beef cow herd in confinement might be unorthodox, but progressive thinking is just the Zoglmann style.

Wife of 18 years Mindy is much the same, and while it may have been his idea, she’s boss lady at the barn. The addition was more than an investment in broadminded cattle-care for the couple. It propelled a career switch for Mindy, promoted from nurse at a hospital in town to cattlewoman. She’s the most familiar face for the barn cows.

Primarily a spring-calving herd, the cattle in their care split their time between pasture and barn. The stocking rate maxes out at 240 cows, but it’s regularly home to 200 at a time.

Innovative problem solving

Hoop barns hold hidden advantages. The confined space creates a more intimate relationship with the cattle, making them easier to feed, handle, wean, calve and breed.

“It’s the easiest weaning we’ve ever done,” says Mindy. “We just shut the gates. There was hardly any bawling since mom was right there. It’s the quietest weaning we’ve ever had.”

In the sweltering Missouri summer, the barn is a comfy 18 to 20 degrees cooler than standing in the sun. Natural, consistent air flow keeps flies, odor and moisture to a minimum, saving dollars on pest treatments.

“The cattle don’t really want out of here,” Zoglmann says, leaning over to scratch one behind the ears. “If we were to open the gates at the end, they would not leave.”

Adding value

The truck clock reads 4:00 a.m. on what’s fixing to be a hot July day and Jeremy Zoglmann wipes the sweat off his brow, pats a donor cow on the rump and sends her jogging out of the chute. He’s a commercial cowman, but does cooperating embryo transfer work with a registered Angus breeder across town. Later today, he’ll be sitting on the tractor seat before checking on his cows. Tonight, you might catch him flying his drone.

He’s not your average Missouri cowboy.

Ancestors relocated his family from Kansas in the 1950s when the farming operation began. Crops may be his heritage, but if you get Zoglmann talking, it’s easy to tell the Angus cows are his passion.

Zoglmann studies his cash flow and watches for opportunities to learn each day, often picking up clues to valuable innovation. Tired of not getting paid for his investment in upper-end genetics, he decided to try retained ownership in 2013.

“I sure don’t have anything bad to say about a sale barn, but it just seemed like we were spending more money on bulls and getting better genetics,” he says. “The calves always sold well, but not as well as I thought they should have.”

Six years have gone by since he’s marketed weaned calves at auction, with no regrets.

The data speaks for itself with closeouts hitting 80% Certified Angus Beef ® brand, including a good share of CAB Prime. In the last three years, a single Select calf appeared on his cutout sheets. For a man feeding an average of 150 head every year, the premiums motivate him to stay the course.

“The best set we had brought $280 per head, over what I could have sold them for at the sale barn,” he smiles. “It’s not like that every year, but it’s impressive to know it’s possible.”

Variety and control in cattle marketing appeal to the calculating cattleman’s mind and the Hy-Plains feedyard team at Montezuma, Kan., is on speed dial. He’s a consistent student of the markets, along with the management techniques that help him through their price swings.

Staring change in the face can be fear-inducing, but when there’s progress to be won, Zoglmann stands ready to place calculated bets.

“In today’s market, if you look at futures and figure a breakeven on these calves, it doesn’t look very appealing to feed them,” he says. “It would be super easy to take them to the sale barn and just walk away, but we have fed these cattle enough to know that $5 to $10-per-hundredweight premium is easily achieved. When you go talking a $10 premium on an 800-pound carcass, it’s a pretty significant difference.”

Vision with strategy

There’s a science to picking winning strategies and he’s constantly adjusting with the times, numbers guiding his way forward.

“We know we have those premiums in our back pocket at about $100 to $150 per head,” he says. “It allows us to play the market a little more because we know what those cattle will do at the end and we have a little bit of cushion.”

Those kind of premiums didn’t pop up overnight, but the result of years of focused breeding. Still, when the first carcass data came back, it was a pleasant surprise.

“Our goal when we started this was to get some kind of value added to our cattle,” he says.

For years, he invested in bulls with strong carcass genetics, preparing his herd to produce cattle that can capture premiums.

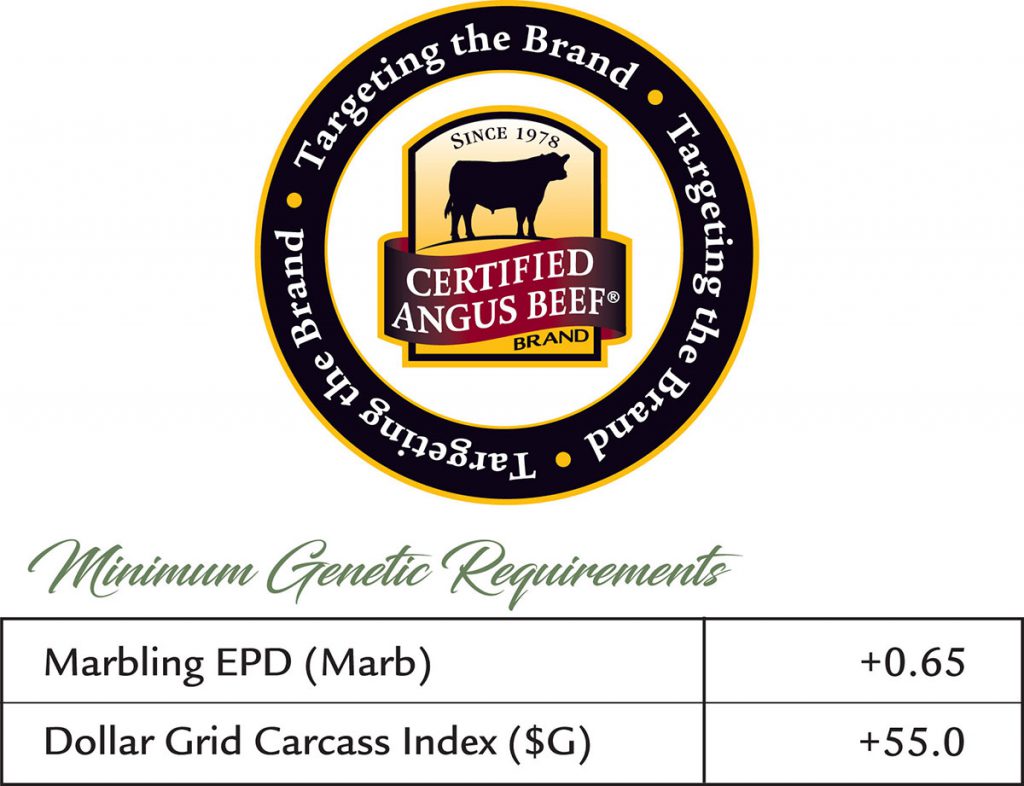

“We try to watch bloodlines, making sure we use something different than we have in the past,” he says. “Then we focus a lot on carcass data and scan data when picking bulls. Carcass EPDs (expected progeny differences) are a big thing for us. We watch marbling and ribeye area on these cattle to make sure we get the best carcass we can get.”

The biggest thing he watches today is carcass data on bull bloodlines. It’s not something every seedstock producer has access to, but Zoglmann says it’s one of the biggest determining factors in his sire selection.

Analyzing extensive herd data influences his maternal selections. Every year, he culls the bottom 20% of the herd and retains the top 20% of his heifers. Choosing the ones that stay is a decision based primarily on genetics.

Zoglmann is confident any will make a quality cow, so lining up the best genetic potential for carcass and ranch performance is a priority. Feeding the heifers that don’t make the cut and lining up cow families with the progeny that grade well points him in the right direction.

“Honestly, our first heifer calves are often the best in the feedlot,” he says.

It’s balanced, data-driven management across his herd that allowed him to add to his bottom line and the pride that comes with creating cattle that create exceptional eating experiences.

“Knowing we raise a product like Certified Angus Beef brand and Prime is pretty rewarding,” he says.

Today it’s small tweaks, not giant leaps Zoglmann works to make.

“We are changing things just a little bit all the time,” he says of their strategy. “It’s not big changes, but little things to make the calves more uniform and higher grading.”

Originally ran in the Angus Journal and the Angus Beef Bulletin.

You May Also Like…

Thriving with Shrinking Supply

Even as the nation’s cow herd contracts, “more pounds” and “higher quality” have been common themes. Specific to commercial cattlemen: It still pays to focus on carcass merit, in addition to other economically relevant traits.

Prime Trends Up

As Prime supplies leapt higher in 2018, continually increasing, the retail grocery sector woke up to the fact that Prime beef cuts could be accessed dependably throughout the year. Prime was no longer reserved for only the high-end restaurant customer. Simply put, creating availability at the grocery level unlocked consumer demand where it hadn’t been tapped before.

2024 Regional Premiums and Discounts

Launched in early August 2024, the USDA’s Live Cattle Mandatory Reporting dashboard is still a relatively new tool. The purpose of the web platform is to keep market participants informed of trends in price distribution across regions and between differing quality and yield classes of cattle.