Never gone dry

CAB Ambassador Award winner’s presence shapes the industry

By: Abbie Burnett

The San Marcos River is not violent by nature. In no hurry, were it not for the thousands of people floating it yearly, it’d be hard to tell if it moved at all.

Yet it does – constantly and steadily. It shapes the path it takes, carving into the earth and making its lasting mark.

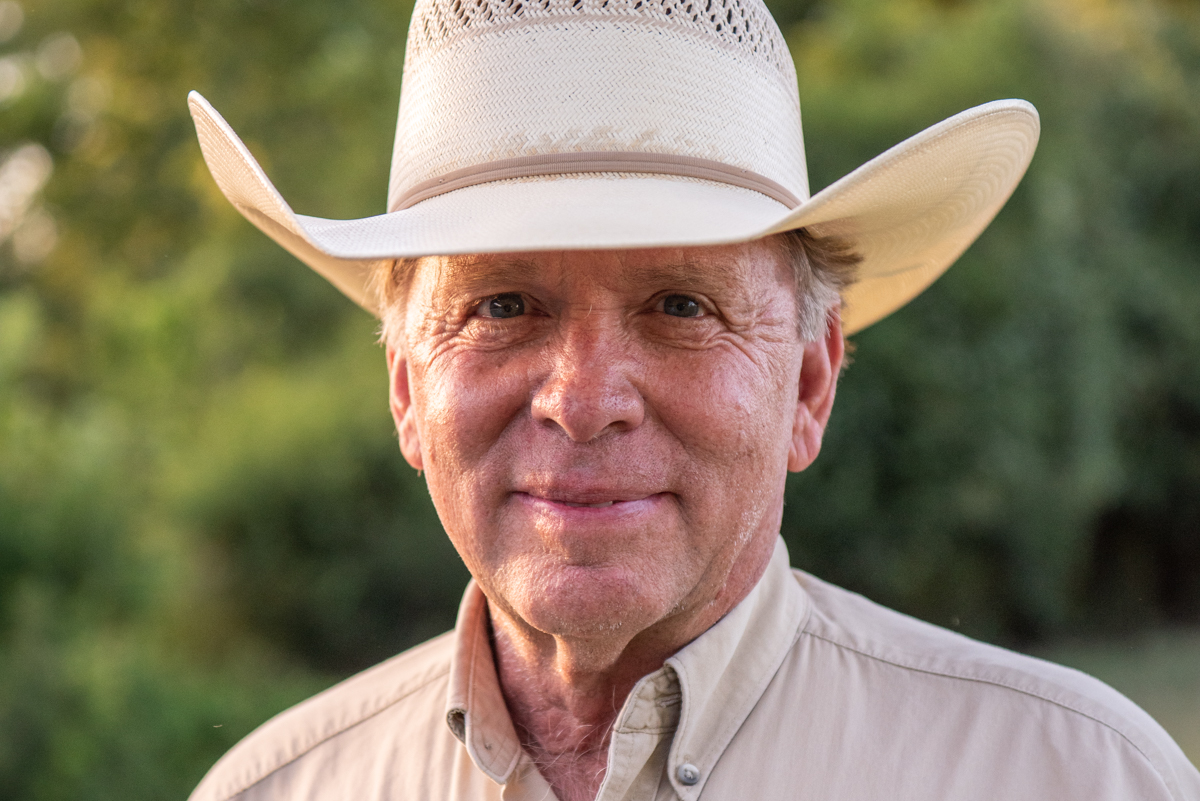

Much like the river in Bodey Langford’s backyard, he’s a gentle but steady force, a constant mark in the cattle industry and the lives he touches.

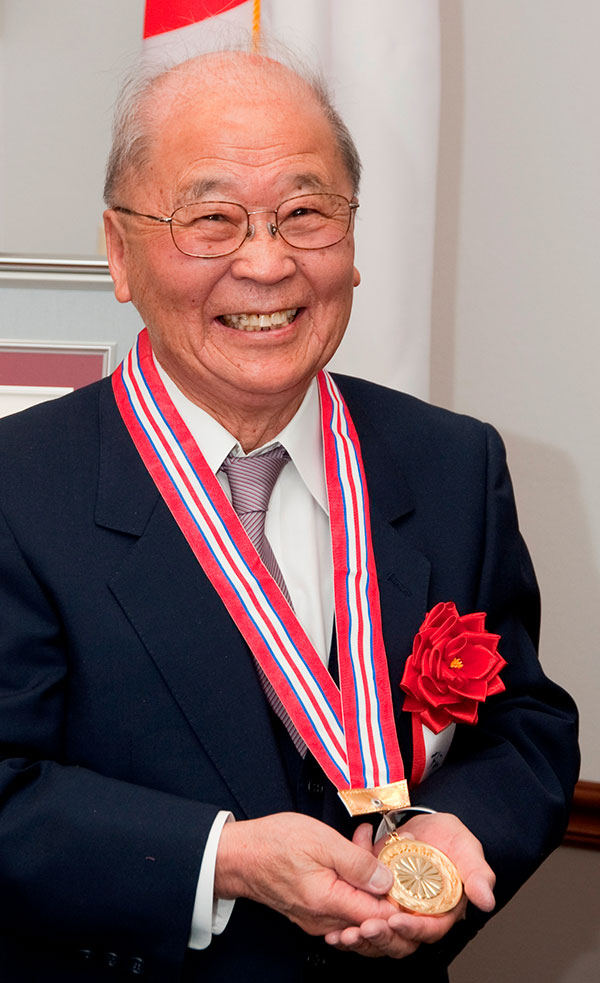

Recently presented the Certified Angus Beef ® (CAB®) brand’s 2020 Ambassador Award, the natural storyteller is heavily involved with the Texas Angus Association and Texas Beef Council. He gets to tell his story to the hundreds who visit his ranch year-round.

Like the natural springs that source the river, he begins his story with those who came before.

Progress and passion

Great-grandfather J.L. Glass helped drive cattle up the trails to Kansas in the 1870s, till he saved enough to file on a homestead of his own in West Texas near Sterling City.

His son Roy inherited some of that land and did well until the seven-year drought of the 1950s. Partway into those hard times, he drove to Craig Air Force Base in Selma, Ala., to visit his daughter Mary Ann and son-in-law Col. Robert Langford and son, Bodey.

“It was springtime, and the oats and the clover were tall and just waving in the breeze,” Bodey recalls. “It was just so green, it hurt your eyes.”

The next day the in-laws put money down for a joint venture on a bankrupt cotton plantation. Saving the herd meant moving cows from Sterling City to Selma, one bobtail truckload of 7 to 10 head at a time.

When the rain returned to Texas, so did they. Those cows and their owner went back to West Texas, but the Air Force veteran bought the property south of San Marcos.

Bodey studied the art of cattle care with his dad or out west at his grandfather’s patient, mellow hand, learning by osmosis. With the untimely death of his father in 1978, the young man looked even more to the west.

Graduating from Texas State University in San Marcos with future wife Kathy, Bodey returned to the nearby ranch to start the Langford Cattle Co. herd, continuing the course his family had set.

When Glass passed away in the 1990s, two inherited Angus bulls led to “the best set of calves I’d ever seen” from the Langford herd, which began shifting course.

“All the people here in South Texas kept saying, ‘Well you’re going to get too much Angus in your herd, and they don’t do well down here,’” Bodey says. “But I never did witness that.”

As that herd became almost full-blooded Angus in the late 1990s, he decided to produce his own Angus bulls and started a registered herd. His neighbors and friends saw the results and began asking for bulls.

“I’ve told people for years that the only real reason purebred cattle exist is to provide high-quality herd sires for the commercial cattle business,” Bodey says. “The females end of it is fun and it’s exciting, but our real reason for being here is to provide those bulls for the beef industry and to create the best carcasses that we can for the packers and the American public to eat. It’s all about the high-quality eating experience.”

Bodey joined with a few other like-minded producers to create the Foundation Angus Alliance in 2006, its 14th annual sale set for February 2021.

“It’s a really good group of guys,” he says. “The unity and integrity of the people that have stayed in it means a lot to me. It means a lot to our customers because we have established a really good customer base in South Texas – primarily commercial cattlemen looking to upgrade their herds with Angus genetics.”

When a drought hit in 2008, tough decisions led to giving up his own commercial herd. After 20 years in the purebred business, he attributes rising demand for his bulls to CAB.

“The kind of bulls I raise will upgrade most types of cattle,” Bodey says. “Through proper selection, it’s not too terribly difficult to get the offspring from my bulls to qualify for the Certified Angus Beef program. So I’m striving to improve the marketability of my customers’ cattle. I want them to be aware of the success of CAB as it makes good business and eating sense.”

Gold standard

Turning the corner at the end of Isidora Trail, a barn with a painted CAB logo on it welcomes you – a sign for the Langfords of the many years hosting events for CAB and others.

“We’ve just gotten to expect having a few events every year, sometimes hosting 300, 400, 500 people out here at a time,” Bodey says. “Everybody leaves happy, with a full belly, and they gain a lot of knowledge not only about the cattle, but about Certified Angus Beef and a lot of the programs that are available to them. So it’s fun, it’s educational and we like doing it.”

The cattleman finds joy in dispelling myths people bring to his ranch.

“The groups that come out here are mostly from urban or faraway places, and a lot of them think that our animals are abused and pumped full of steroids and antibiotics,” he says. “It’s a pleasure to me to be able to tell them the truth.”

The truth involves Bodey’s judicial use of vaccines, nasal and topical sprays, fly tags and the occasional antibiotic – all to create a high-quality life for the animal.

He once hosted Temple Grandin in his home. Her philosophies are his philosophies in handling cattle.

“Anybody that comes to work for me that’s going to help process or work any of my animals gets a pretty good schooling before they ever get in my cow pens,” Bodey says. “I almost don’t want anybody talking in my cow pens, much less yelling or screaming or whistling because I can see the difference in behavior and health in cattle that have and haven’t been handled that way. I know what stress does to animals and humans, and I can see it in their performance.”

Different times, different storms

At another station on ranch tours, the San Marcos riverbank, he explains what farmers and ranchers do to benefit the land, the river and the world around them.

He also shares candidly the challenges he faces that his father and grandfather never had.

People encroaching from Austin, San Antonio and everywhere in between threaten his life and livelihood. The more concrete, the more water rushes down the river, the more flooding.

Bodey built his first home by hand, only a few hundred yards downriver. Brick by brick, he poured his all into the place he would bring Kathy home to and where they’d raise their two daughters, Anna and Callie.

Since the original fishing cabins in 1919, water never entered living quarters, but in 1998 the river rose and overtook their first house. The family had already moved upstream, but it was like watching memories die.

Three more times the house would flood, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) restored all but the last one. It now sits condemned at the edge of the property.

“It was our home where we raised our babies, and it’s really disheartening to lose it,” Bodey says.

Now the water creeps toward their current home, like a clock ticking to the inevitable.

It was more than 4 feet above the 100-year mark when built. Now, it’s several feet below that.

When the waters would come, the Langfords used to have a few hours to plan. That’s been cut in half when rains swoop into San Marcos.

On the east side of the ranch, past the fields where their cows graze, a creek will merge with the San Marcos river and surround their home like a tiny island.

There’s little they can do to prevent damage. Cattle are moved first, and Bodey’s no-till practices help conserve soil and root structure. Kathy manages to keep their kitchen stocked and family photographs are kept upstairs.

“Fortunately, we have not had river water in the house,” says Bodey, “and I’m hopeful that we never do. But it’s sure been close a lot of times.”

Flooding isn’t the only thing bringing change to Langford Cattle Co.

Bodey and Kathy remember seeing more stars and fewer electric lights on the horizon early in their 37-year marriage. The dawning sun had no competition. Now there’s a 6-lane toll road 1,500 feet from their house, and two cell towers in the sun’s rising path.

Bodey knows the wildlife on their property would be displaced when the inevitable developer gets hold of it.

Their daughters aren’t planning to return to the ranch.

“If this would work for them, they would be here,” Kathy says. “But there’s so much to consider – their children, where will they be in school? What’s to become with the subdivisions that are coming in? And the river just encroaches further with every flood. The kids don’t want to be here for that, and I don’t blame them.”

Competition from developers would blow past any possible margin of return from ranching.

“It’s disappointing,” Bodey admits. “More disappointing that somebody will not continue the genetics and the herd that I’ve built than the disposal of the land; that’s inevitable in this region.”

What’s in a legacy

Bodey and Kathy have come into contact with thousands of people through ambassadorship and that impact will continue on – much like that river in the backyard.

“I can’t even begin to count how many people we’ve had out here from foreign countries and other states and people that aren’t in the cattle business, but are recipients and marketers of our products, meat purveyors, and restaurateurs and chefs, and that sort of people that make our business work,” Bodey says. “When they know what we’re really doing, it helps all of us.”

That extends to fellow cattlemen. President-elect of the Texas Angus Association, it’s his second time in five years.

“When Bodey was younger, he may have gone to somebody for advice, but now he’s reached that point where people come to him for advice,” Kathy says. “I’ve seen that progression. It’s very touching.”

When he heard the CAB Ambassador Award news, he said he about fell out of his chair.

“I just sat back, took a deep breath, fought back some tears and said, ‘Hallelujah, and thank you very much.’”

He says it’s a tremendous honor, but gives the credit elsewhere.

“I don’t believe any of this stuff we do and all the great things around us would be possible without the hand of God,” he says. “He’s the one that blessed us and allowed us to live this lifestyle and make our living working with cattle. We’re certainly blessed beyond all measures.”

Sidebar:

Ambassador for the Brand

Bodey and Kathy Langford have hosted many events for Certified Angus Beef LLC (CAB) for Saltgrass Steak House and Sysco Houston. But when CAB’s Kara Lee called in 2018 with a request, it was a new challenge.

The brand’s Foodservice Leaders Summit was set for Austin in 2019 and they needed a ranch to visit.

“I really wanted to go to Bodey’s,” Lee said. “But the day we wanted to come was two days before his bull sale.”

She decided to call anyway and left the decision up to him. After proposing what they wanted to do, all she heard was silence on the other end of the line. Lee thought for sure a “no” was brewing.

“Oh, I think we can make it work. Can’t afford not to,” Langford finally replied.

It was this consistent sacrificial response that led to the honor of the CAB Ambassador Award.

You May Also Like…

Marketing Feeder Cattle: Begin with the End in Mind

Understanding what constitutes value takes an understanding of beef quality and yield thresholds that result in premiums and/or discounts. Generally, packers look for cattle that will garner a high quality grade and have excellent red meat yield, but realistically very few do both exceptionally well.

North Dakota Partnership Earns CAB Progressive Partner Award

The Bruner and Wendel families earned the 2023 CAB Progressive Partner award by selling high-quality beef through Dakota Angus, LLC, as part of the CAB Ranch To Table program. They focus on their commitment to quality, data-driven decisions, achieve impressive CAB and Prime percentages and offer high-quality beef directly to consumers in their communities.

Kansas Ranchers Recognized for Sustainability Efforts

Kansas’ Wharton 3C Ranch thrives despite droughts, winning the CAB 2023 Sustainability award. The data-driven, quality-focused approach of first-generation ranchers, Shannon and Rusty Wharton, yields 100% CAB cattle. Their commitment to sustainability and industry collaboration sets a bright future for the cattle business.

It’s not, as Wilson would put it, “hippy woo-woo.” He has the data to prove it works, boiling down the economic input into gains and head-days in pasture. Limited input, maximum production output tracked on a per-head basis gets the most for his resource dollar.

It’s not, as Wilson would put it, “hippy woo-woo.” He has the data to prove it works, boiling down the economic input into gains and head-days in pasture. Limited input, maximum production output tracked on a per-head basis gets the most for his resource dollar.

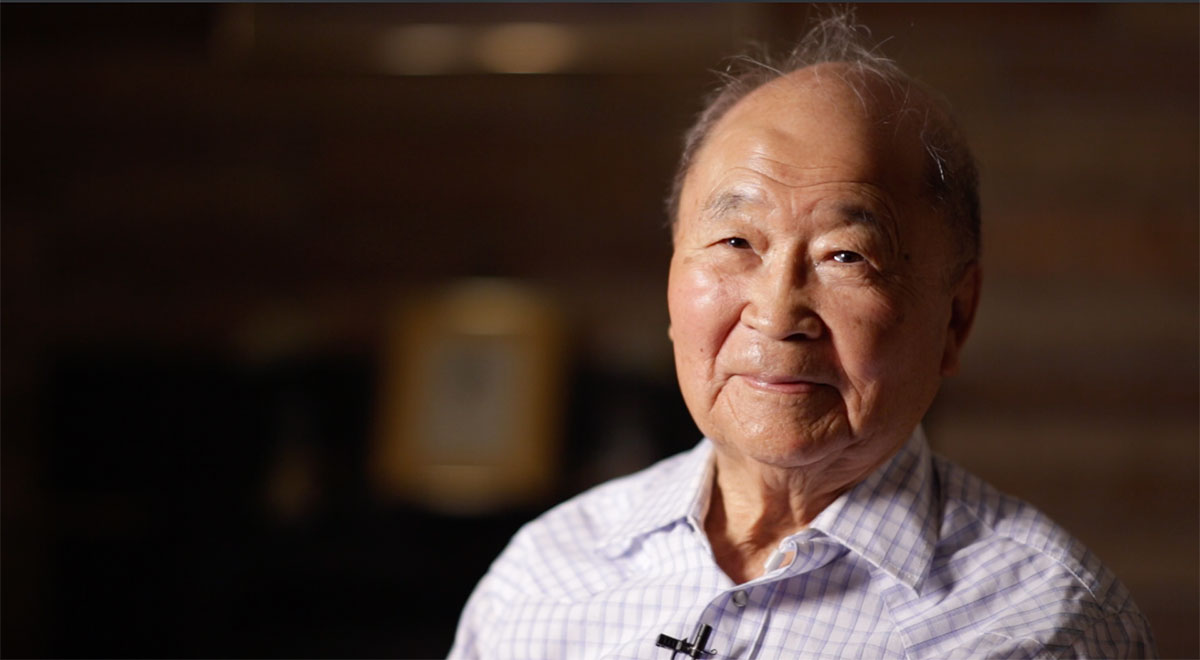

While these accomplishments and their industry impacts are vast, Matsushima is more proud of his work as a professor, particularly when it comes to his students.

While these accomplishments and their industry impacts are vast, Matsushima is more proud of his work as a professor, particularly when it comes to his students.