M&M Feeders wins CAB honors

by Miranda Reiman

September 24, 2020

“Honesty is the best policy.”

For brothers Mel and Marvin Huyser that’s not just an old saying. It’s a code they live by, the way they run their cattle feeding business and how they lead their families.

“Honesty is the best business advertisement you can have,” says Mel Huyser. “We have always stuck to our guns on that. It has always paid off.”

Customers come from word-of-mouth or longtime connections. In turn, the feedyard gets more high-quality cattle and helps create more of them.

“It’s about treating people right, treating people with integrity,” says Mel’s son Daron, who joined the family business in 2005. “We want to take care of the customer cattle the same way we would take care of our own—and even better—because their trust is in us to take care of their cattle.”

For building beneficial relationships and their drive to produce the best, M&M Feeders earned the 2020 Feedyard Commitment to Excellence Award from the Certified Angus Beef ® (CAB®) brand.

The best hard choice

In the early 1990s, the Idaho family saw inputs and markets moving toward the middle of the U.S., so one branch decided to do the same. Mel and Connie relocated to Elm Creek, Neb., in 1992, while Marvin and Reeta stayed put.

“We could see the cattle industry was changing,” Mel says. “The packers were out here and the corn was out here and it was a good move for us.”

It took patience and prayer, and a big dose of faith.

“We’ve been blessed that we’ve been given this area, and this facility, and blessed with my kids because they love the business.”

Daron went off to college to study animal science, Marvin managed commodity trading from Idaho and Mel ran the feedyard. They wanted to expand, but the right opportunity was just out of reach—until 2015.

“It was like getting that winning lottery ticket,” Daron says. “You have the opportunity to do what you want to do, to come back, be large enough to establish and carry a family, take care of customers. I thought, ‘Let’s jump in with both feet and go.’”

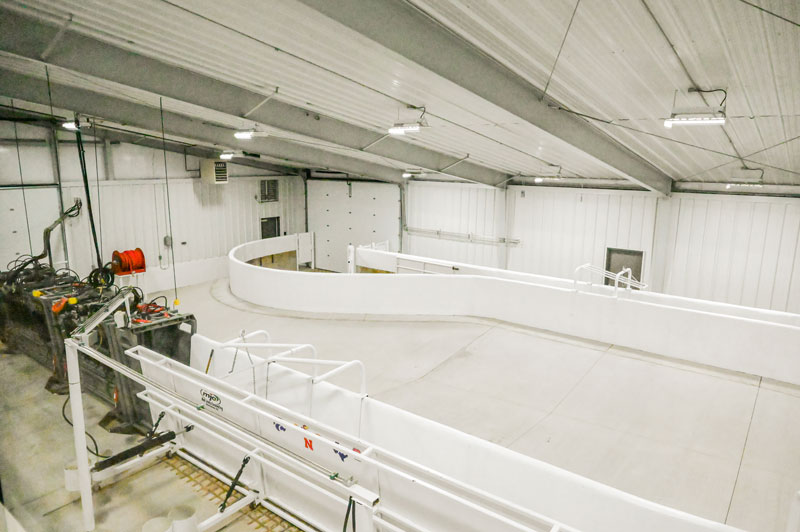

They purchased the yard at Lexington, where Daron now manages operations with his dad. Nearby Daron and wife Hayley raise their three boys. His sister, Jamie, tackles the daily tasks at Elm Creek.

“It’s somebody in the family feeding the cattle, taking care of the cattle day to day,” Daron says. “We don’t have to sit and look off a computer and tell you exactly whose cattle they are. We have relationships; we talk with the people weekly.”

In almost no time, they had the 6,500-head second location full of customer cattle and their own.

Raising the feeding kind

A friend at the local café nudged Daron to apply for the Young Farmers and Ranchers loan that kick-started the herd. But he credits their genetic supplier, Connealy Angus, Whitman, Neb., with getting them set for success.

“They helped us see the value of genetics,” Daron says. “We could see the improvement starting with the calves carried all the way through onto the carcass traits and the different premiums that we could get.”

They’ve improved calf vigor, disposition and mothering ability, too.

The Huysers artificially inseminate the entire herd, calve early and hit the April market with 14-month-old finished cattle. Most go right up the road to Tyson, where they’ll often bring $5 to $10 above the market and reach 60% CAB acceptance, not counting another 10% to 15% Prime. Trying to hit that earlier market, they sell “a little green,” Daron says, noting 10% yield grade 4s.

“Certified Angus Beef has been a way that we can add more value to our carcass,” he says, while also securing demand by meeting consumers’ needs.

Having “skin in the game” helps them share what’s worked in their herd, along with the carcass and performance data. It’s helped them narrow their purchasing orders, too, transitioning from unknown genetics to those with more reliability.

“We’ve seen the value of buying cattle off of one ranch or off of a bigger group of cattle from people who are really invested and improving their genetics,” he says. Verifications programs like AngusLink® show which cattlemen are probably already doing all the little things that add up.

Knowing the cattle’s history gives them confidence, but with capital invested at each turn, it still takes more than a little faith.

“We prayed that if it was God’s will, that the doors would open, and they did open,” Marvin says. “And the biggest thing was when they did open, to have the faith to walk through the door and keep going.”

CAB recognized its 2020 honorees at the brand’s virtual annual conference on September 23 and 24.

You may also like

Feeding Better Cattle Better

Not everyone is cut out to be a cattle feeder. It’s an art and a science that comes with a need to overcome risk. Wayne Carpenter fed his first pen of steers in 1980 and lost money. But he stuck with it. Today with their sons’ families, he and wife Leisha run the 15,000-head-capacity Carpenter Cattle Company.

You, Your Cows and Their Feed

Expert guidance from Dusty Abney at Cargill Animal Nutrition shares essential strategies for optimizing cattle nutrition during droughts, leading to healthier herds and increased profitability in challenging conditions.

Marketing Feeder Cattle: Begin with the End in Mind

Understanding what constitutes value takes an understanding of beef quality and yield thresholds that result in premiums and/or discounts. Generally, packers look for cattle that will garner a high quality grade and have excellent red meat yield, but realistically very few do both exceptionally well.