The prime of his life

Arizona commercial cattlemen awarded for commitment to excellence

Story and photos by Morgan Boecker

October 2021

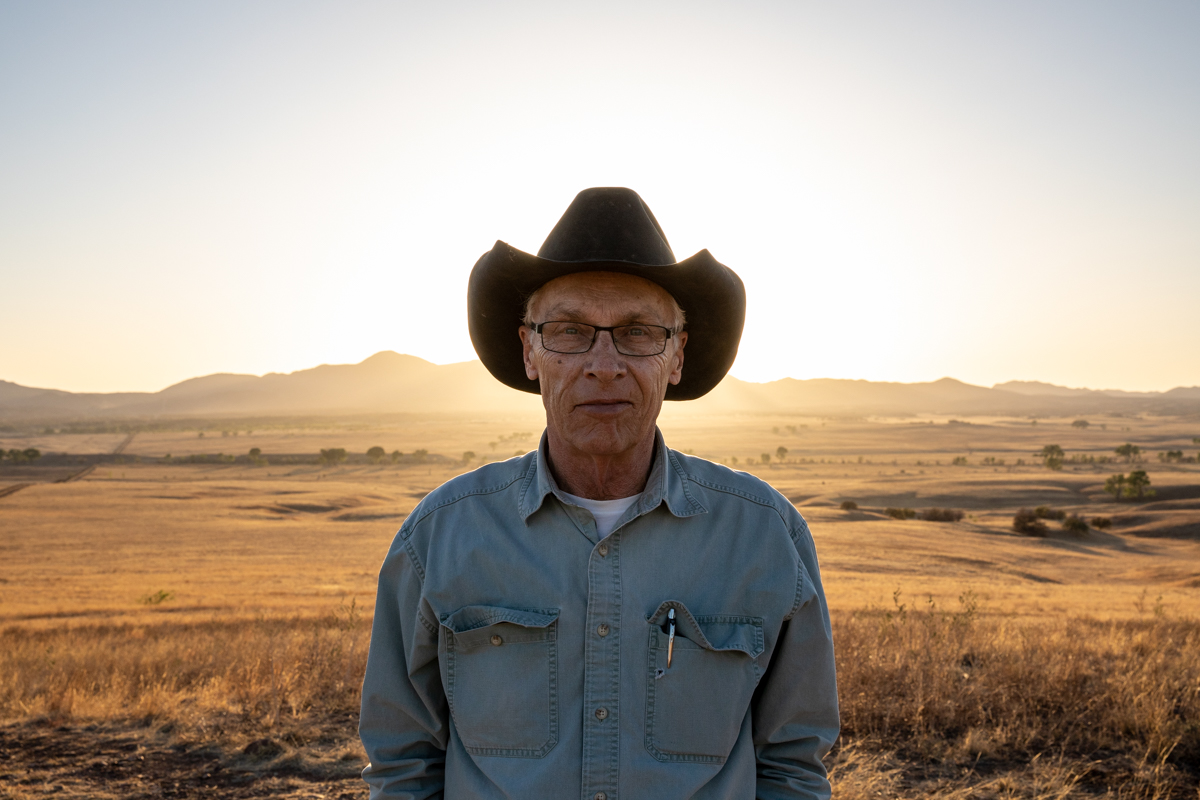

Ross Humphreys’ adept gait tells of many days in and out of the saddle checking his herd, fence lines, water tanks, and grass availability. Yet at 72, he can still drop down and roll under the barbed wire fence quicker than most men half his age.

But Humphreys is not your typical cowboy. He’s a chemist, book publisher, family guy, conservationist, and rancher.

He wears many hats, but his black felt wide brim fits most naturally, shading him from the sun at San Rafael Cattle Company, south of Patagonia, Ariz., along the Mexico border. When off the ranch, you can find him in Tucson managing stocks and his publishing company.

Grit in every venture makes him a successful businessman, and his unrattled spirit makes the best of challenges. However, it’s his relentless drive for raising high-quality beef that earned him the Certified Angus Beef (CAB) 2021 Commercial Commitment to Excellence Award.

A different background

Humphreys grew up an army brat, traveling and moving most of his childhood. He went to college on the east coast and earned a degree in chemistry.

After a career as a newspaper photographer, chemist then a metallurgical engineer climbing smokestacks, he decided to go back to school for a Master of Business Administration. That sent him to New York for a new career in strategic business consulting.

In 1980 he moved to Tucson to manage a newspaper family fortune and later launch a cancer diagnostics company. Along the way, he and his wife Susan bought Treasure Chest Books, adding “book publishers” to their resume.

There was also a short stint when he found a new job study, consulting ranchers with the Malpai Borderlands Group.

In 1999 at 50-years-old never having owned cattle or managed a ranch, he divested from his cancer diagnostics business interest and bought San Rafael Cattle Company. Admittedly, he took an unusual path to the cattle business.

“The ranch had been in one family’s name for almost 100 years,” Humphreys says. “I stood on one of the hills with my older daughter and said, ‘Anybody could run a cow on this place because you can see her wherever she is.’ So that’s how we got started.”

Consistent little changes

Most ranchers learn from their parents or grandparents, but Humphreys went straight to the University of Arizona and bought a Ranching 101 textbook.

He started out doing what many of his neighbors did, raising black baldies and selling calves at weaning. Always curious, his questions led to new acquaintances, and Mark Gardiner, of Gardiner Angus Ranch in Kansas, became his teacher and connector.

“I’ve hardly ever spent any physical time with Gardiners,” Humphreys admits, “But if I called them up, they’d spend two hours on the phone with me answering questions.”

They guided Humphreys, never telling him what to do but pointing out issues to consider – planting ideas that would turn small changes into significant results.

“When I think of Ross, I think of the book called Moneyball, because he looks at the numbers,” Randall Spare, Kansas veterinarian and Humphreys’ mentor, says. “He knew the expected progeny differences (EPDs), and he knew focusing on those numbers would work.”

Humphreys leaned on sound science and good information – it’s what drove him to the business breed. No ranch decision is made without running some math and looking at a spreadsheet.

That mindset transformed his herd when profit-driven cattle marketing, like retained ownership, was gaining popularity.

His Hereford-Angus cows quickly shifted after he started buying registered Angus bulls from Gardiner. He focuses on selecting for calving ease, docility, ribeye area, and marbling to pursue balanced cows that can raise replacement females and a calf crop that produces the best beef.

In 2013 Humphreys attended a lecture in Kansas about genetic testing. Looking at the other cattlemen in the room who he had watched buy bulls the last decade, he thought, “I’m definitely not in their club.”

He started testing all his cows and each annual set of replacements and watched the average genetic profile of his heifers climb.

Steady progress built on buying a little better bull than the year before, Humphreys confirms his plan works with results at the feedyard. Loads of his fed cattle have improved from 20% Prime in 2013 to 95% CAB or higher, including nearly 85% Prime today.

Emphasis on uniformity makes it easier for his feeding partner to manage his cattle and achieve those results.

Humphreys determined he could be a cattleman who buys cheap and sells cheap, conserving financial resources, or he could sell food.

“I decided that I want to raise beef,” he says. “My goal is to try to produce the best carcass I can. So, I keep trying to nudge up my cow herd so that the calves will be even better the next time.”

Preserving today for tomorrow

Conservation is as much part of the San Rafael story as the cattle. Named after the San Rafael Valley, the ranch is nestled in Arizona’s high desert country bordering Mexico. It’s the north end of a rich ecological site that looks like the Great Plains and is home to various plants and animals, many on the endangered species list.

“We’ve implemented protection and re-introduction plans and learned so much about the animals and plants that live here,” Susan says.

“Ninety-five percent of this ranch is perennial native grasses,” Humphreys says. “We are the last shortgrass prairie in Arizona.”

The Nature Conservancy established two conservations easements on the ranch the year before Humphreys bought it, making the ranch an attractive investment for the couple.

“We’ve always been interested in conservation,” Susan says. “And that was one of the reasons we bought this place.”

Conversations with conservation groups ensure that the ranching operation, endangered wildlife, and habitat are protected from housing or industrial development. The easements with Arizona State Parks and the Nature Conservancy led to work with U.S. Fish and Wildlife and Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

“I think that this is the most beautiful, rich biological valley in Southern Arizona,” Humphreys says. “As a student of NRCS, I know that we can out climate anybody else in my ecological site.”

The most important habitats on the ranch are water sources, including the Santa Cruz River, several springs, and stock tanks. The endangered Sonoran Tiger Salamander is only found in stock tanks in the San Rafael Valley. Humphreys has developed water sources with support from NRCS grants – creating a mutual benefit for the cattle and wildlife.

“The salamanders probably wouldn’t be here if not for the stock tanks,” says Doug Duncan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist. “And that’s where the value of livestock in this valley really benefits many of the aquatic species.”

Wetter years to come

Environmental investment is key to Humphreys’s long-term goal of sustaining the land as a working ranch. Collaboration with NRCS helps him set standards and objectives for improving the land and preparing for years when Mother Nature is unkind. The current Southwestern drought continues to challenge his resources.

“After two years of severe drought, the ranch isn’t beautiful anymore,” Humphreys says.

Thoughtful and strategic management of resources is vital in an area that seems to get dryer every year. The 34 square miles of the ranch is split into 25 rotational grazing pastures. He moves the cattle once 40-50% of the grass is consumed and returns for re-grazing only after it rains.

Even with intensive management, the land still needs water. As a result, Humphreys sold roughly 65% of his cow herd this year.

“It was terrible,” he admits. “Except I sold them to two of my best friends.”

Unsure if he will ever get back to pre-drought herd numbers, he remains committed to this final career as a rancher.

“I want to come home to a beautiful place,” he says. “I started doing this when I was 50, but I like the work. I like the cows.”

Ever the student, he meets each new challenge with a thirst for knowledge, determined to sustain, and focused on raising the best, one step at a time.

Originally published in the Angus Journal and Angus Beef Bulletin.

You may also like

An Unforgiving Land

What makes a ranch sustainable? To Jon, it’s simple: the same family, ranching on the same land, for the last 140 years. The Means family never could have done that without sustainability. Responsible usage of water, caring for the land and its wildlife, and destocking their herd while the land recovers from drought.

Double Down on Angus

South of Calgary, Alberta, brothers Austin and Malcolm Cross carry on a century-old family history. Their great-great-grandfather staked his future on this land. Today, the Cross brothers are building one of their own—with Angus cattle that not only perform in the harsh environment but consistently meet the highest standards for beef quality.

A Means to an End

For Willis Ranch, the best Angus cattle thrive in the high desert and produce calves that can become productive replacement females or high-quality carcasses. Every year, calves are better because of their investment in tools like GeneMax and AngusLink. But behind it all is one man’s perfectionist mindset that keeps the entire family moving in the same direction.

It’s not, as Wilson would put it, “hippy woo-woo.” He has the data to prove it works, boiling down the economic input into gains and head-days in pasture. Limited input, maximum production output tracked on a per-head basis gets the most for his resource dollar.

It’s not, as Wilson would put it, “hippy woo-woo.” He has the data to prove it works, boiling down the economic input into gains and head-days in pasture. Limited input, maximum production output tracked on a per-head basis gets the most for his resource dollar.