2019 Feedlot Commitment to Excellence

All-in cattle feeding

Timmerman family receives CAB honors

Story and photos by Miranda Reiman

September 25, 2019

They were raising children with diverse skillsets and diverging dreams.

Veteran cattle feeders Norm and Sharon Timmerman, of McCook, Neb., encouraged their children to follow their own passions, and they did. After college, Jason started with Timmerman Feeding near Omaha, while CPA Kristin ran her own accounting firm and Ryan pursued a degree in business management with a sports and recreation option.

Today, they have all returned to the family business that now includes, Jason and Wendy, Kristin and husband Jeff Stagemeyer, and later Ryan and wife Nicole.

“It’s nice to be that good of friends with your family members, who like to work together,” Norm says. “It all fell into place.”

The family brings a shared trust and camaraderie to the work they do for the feeding company they jointly own: NA Timmerman Inc. They started in 2012 with yards at Indianola, Neb., and McDonald and Colby, Kan., now also including locations near Holyoke and Sterling, Colo., with a one-time feeding capacity of 80,000 head.

For their dedication to grid marketing, feeding premium cattle and a call to doing the best job every time, the Norm Timmerman family received the 2019 Feedyard Commitment to Excellence Award from the Certified Angus Beef ® (CAB®) brand.

The quality kind

“There are a lot of small feedlots that specialize in the high-quality type, but larger feeders don’t always have the benefit of picking and choosing what cattle they feed. They need to keep the pens full and often feed a wide variety,” says Paul Dykstra, beef cattle specialist for the brand. “They’ve really evolved over the last 20 years or so, under Jason’s vision, to procure cattle that will do well on a grid.”

In 2005, the Timmermans tested grid marketing with sales of 2,100 head on a Cargill formula. Today that number is closer to 150,000 annually. It’s changed their procurement and it’s changed their harvest targets.

“We keep the feedyard full and we manage our risk and we try to maximize our performance to the best of the ability of our cattle,” he says, “versus the old cash system: hurry and sell, or wait and make them too big. When they’re ready, they’re ready, we just keep rolling and just manage the risk on the other side of it.”

Despite a difficult winter and early spring for Great Plains cattle feeding, the Timmerman marketings still hit 38% CAB and Prime for a three-month average into this summer. In recent years with more cooperation from Mother Nature, their branded quality numbers have been significantly higher across the board.

Jason and Jeff have extensively used artificial insemination on the 700-head cow herd they own together, which shows them the impact of genetics on the final results. Three years of feedyard data on the progeny reveals more than half of make CAB and Prime.

“When we get a pen of high-grading cattle that have a lot of CABs, it directly affects us,” Jason says, “because it’s money in our pocket.”

The entire Timmerman family is committed to excellence. See why we love them and their quest for quality.

Extra effort

“Hard work will give you a lot of luck,” Norm says.

Pen maintenance, feed delivery and cattle health monitoring—they all add up.

“There is no room for error. It’s a sole responsibility,” Ryan says. “The job we do at the feedlot impacts our customers. There’s a lot of money involved…it’s their livelihood.”

It’s not like a Timmerman to let people down.

“These are the things that are important to the Timmerman family: their faith, being a good family member, working hard at what you’re doing,” Kristin says.

She and Jeff bring a fresh perspective to the finances, giving purchasing advice and making insurance decisions.

“My dad and I knew the outside very well, but needed someone in the back that could complement us–luckily we had family that could do that,” Jason says.

Leo’s legacy

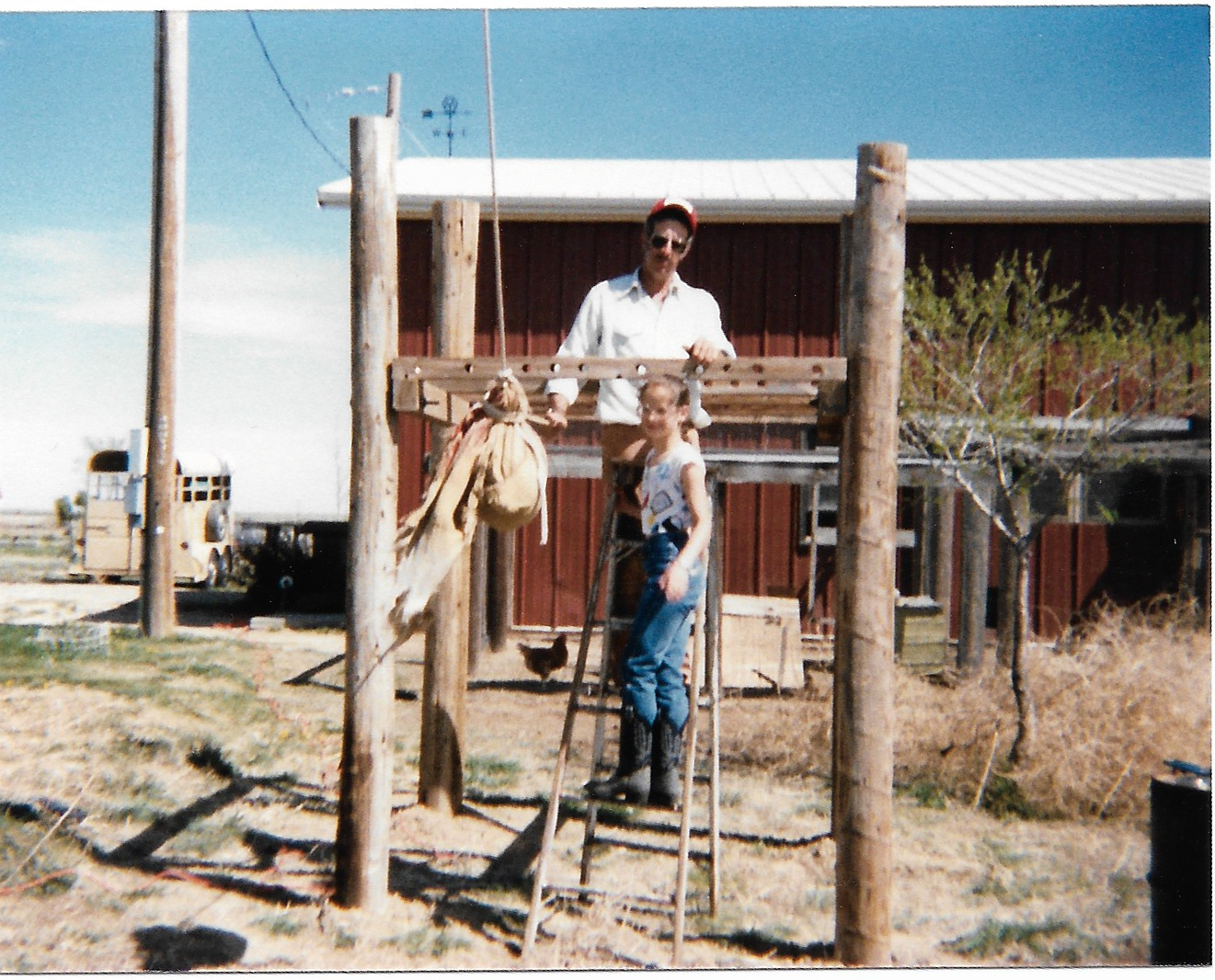

They had a good example of seeing partnership in action. Timmerman Feeding of Springfield, Neb., started by Leo Timmerman, was into the hands of the next generation, brothers Gerald, James, Ronnie and Norm, when they expanded to Indianola, some 250 miles west.

“This was a farm and we built it from scratch. The office started in our trailer house, where we lived,” Norm says, giving credit to Sharon. She kept the books there by day and made it a home by night.

By this decade, with the third generation involved, it was a natural time to let each Timmerman branch individually exercise their entrepreneurial spirit.

They gave their children the opportunity Leo Timmerman gave them.

“It evolved to where I was doing more, more and more,” Jason says, noting the risk management shifted to him through the years. “Then it’s how do you keep it organized? Trial and error. Mistakes, mistakes, mistakes.”

Years like 2014 remind them it’s fun to make money. Years like 2015 keep them humble.

“I don’t think it will ever be easy. You’re in an environment dealing with people, dealing with Mother Nature. You’ve got the element of risk,” Jason says. “It will never be easy, it’s just about how you manage your way through it.”

History says they’ll do it. Being a Timmerman means they’ll do it well.