Nice to Meat Ya: Bob Boliantz

“Eight head of cattle – $893 … total,” he laughs. “Obviously, my father was a much better buyer than I am.”

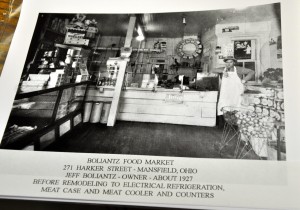

Emil Boliantz had a knack for picking the right cattle and knowing which farmers he could count on to supply his Mansfield, Ohio, meat packing plant with high-quality beef. The son of butcher shop owners, Emil grew up in the meat business, turning a youth’s worth of knowledge into a successful meat packing venture before passing the trade to his son, Bob.

Today, although the era of purchasing a steer for just over $100 has long since passed, many of the same practices employed by his senior are still in place at Bob Boliantz’s plant, E.R. Boliantz Co., located less than 20 miles from his father’s, in Ashland.

“It’s about relationships,” Bob says. “If you build relationships with the farmers and with the right people who can help them, you’re going to have the right kind of cattle to work with.”

Like his father, Bob has made a career of hand-selecting cattle and building a reputation for quality. He works with a slew of farmers in and around Northeast Ohio whom he knows raise cattle to hit a high-quality end point – including a good amount that qualify for both the Certified Angus Beef ® brand and Certified Angus Beef ® brand Prime.

Bob has played a major role in the quality beef movement in Ohio – and not only from a processing perspective.

When he saw a greater need to increase the number of quality-fed cattle, he began working with Dr. Francis Fluharty from The Ohio State University. Together, the two offered classes for farmers and ranchers to teach them better feeding practices so their cattle would grade out higher.

The results? It’s safe to say the proof is in the pudding.

Boliantz’s beef can be found in a host of retail stores around Ohio, including the source of 15-store Buehler’s Fresh Foods’ “Proudly Raised in Ohio Certified Angus Beef ® brand” program.

Perhaps more visibly, it’s Boliantz beef that’s served to guests at the critically-acclaimed, James Beard award-nominated Greenhouse Tavern in downtown Cleveland, where the emphasis on fresh and local is melded with trendy and edgy food presentations by Chef Jonathon Sawyer.

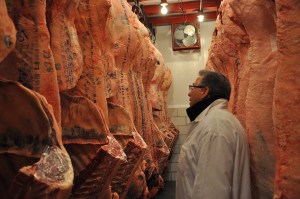

In a day and age where most beef comes from large-scale packing plants, Bob still does it the old-fashioned way. His team of butchers harvest the beef from start-to-finish, while his sales people do their job to ensure that the well-marbled hunks of meat have a home.

“Right now our biggest problem is cooler space,” Boliantz says. “We can handle more cattle than we do now, but we’ve got to keep it moving. Back in the day, it was no big deal because you could sell it by the whole carcass. Today, though, everybody buys boxed beef, and that takes up a lot more square footage.”

Though markets, trends and consumer preferences may change, one thing that isn’t going away is demand for great beef. There’s something to be said for the tried and true.

And Bob Boliantz is living proof that, sometimes, the old methods are still the best methods.

PS–To catch up on all the other “unsung heroes” we’ve covered this month, check out these links:

- Introduction: Nice to Meat Ya

- Day 1: Ashley Pado

- Day 2: Scott Redden

- Day 3: Jesse Stucky

- Day 4: Bridget Wasser

- Day 5: Amanda Barstow

- Day 6: Josh Moore

- Day 7: Ruth Ammon

- Day 8: Bill Tackett

- Day 9: Dan Chase

- Day 10: Danielle Foster

- Day 11: Eric Mihaly

- Day 12: Jennifer Kiko

- Day 13: Mark Morgan

- Day 14: Meg and Matt Groves

- Day 15: Rod Kamph

- Day 16: Jonnie Schreffler

- Day 17: Brent Eichar

- Day 18: Alberto Diaz

- Day 19: Larry Kuehn

You may also like

Gardiners Highlight Service, Strength at Foodservice Leaders Summit

Mark Gardiner and his son, Cole, of Gardiner Angus Ranch offered a boots-on-the-ground perspective for CAB specialists attending the annual event, designed to deliver resources that help train foodservice teams and serve consumers at a higher level.

Chef Coats and Cowboy Hats

Two worlds collide, with one focused on raising the best beef and the other crafting dishes that honor it. This innovative program unites students from Johnson & Wales University and ranchers from across the United States, offering an immersive look at the beef industry.

Mark Ahearn Completes Term as CAB Board Chairman

Mark Ahearn admits his role as the chairman has meant a lot to him and his family. He expresses gratitude to those who believed in him throughout the past year and looks forward to seeing the future successes of the premium beef brand.