If not born wild or mishandled, dollars add up

by Morgan Slaven

Nobody wants cattle with too much “attitude,” but it takes focused genetics and handling to improve docility in a herd.

“We’ve always tried to be careful about selecting bulls for disposition,” says Roger Jones, of Tri-Tower Farm, near Shenandoah, Iowa. “It’s very important to us to have a cowherd that we can handle, without a lot of wild calves in it. You know, the cattle do better in the feedlot when they aren’t wild.”

Since he operates both enterprises, Jones knows how those issues carry from the field to the feedlot.

“We definitely notice pens of cattle that come in that are wilder,” he says. “Even just one or two individuals, especially when they first arrive, can keep a whole pen stirred up.”

Jones is a cooperating feeder for the Tri-County Steer Carcass Futility (TCSCF), which provides performance and carcass data so that cow-calf producers can improve management. The Futurity began in 1982, charting temperament scores first analyzed by Certified Angus Beef LLC (CAB) nine years ago and recently updated in a Black Ink Basics report.

“Calm cattle reduce injuries and facility damage, stay healthier, perform better on feed and earn higher grid premiums,” says the technical summary, “Nervous Cattle Wreck Profit Potential.”

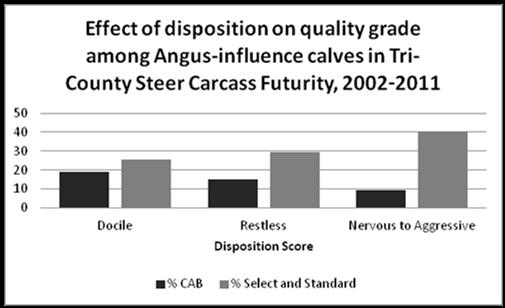

The data analysis spans 10 years of TCSCF data on more than 65,000 cattle fed in 14 cooperating feedlots. It concludes the docile cattle earn $57.69 per head more on a grid compared to their aggressive pen mates. Part of that comes from the higher Certified Angus Beef ® brand acceptance rate for calm cattle (see chart).

Sally Northcutt, American Angus Association genetic research director, says with that kind of economic impact, it pays to understand the breed’s Docility EPD (expected progeny difference).

More than 490,000 registered Angus cattle now include that “DOC” EPD in their records, with an average of 9, and more docility scores are being collected all the time, with weekly updates.

“One of the nice parts of working with docility is that it is moderately to highly heritable,” Northcutt says.

TCSCF Manager Darrell Busby agrees much can be done through genetic selection, but he points out management still makes a big difference, and that includes handling.

“We have feedlots that check cattle on horseback, on foot and on four wheelers. They’re successful in any method,” he says. “It’s the people doing it that are the most important.”

There’s a positive impact in the feedlot when producers make a point to walk through their cattle every day and participate in low-stress handing workshops.

“We see a general improvement in disposition in the data we’ve collected,” Busby says. In turn, that leads to better gains and quality grades.

Northcutt encourages breeders to use DOC to enhance their overall balanced selection program.

“Some people originally saw docility as a convenience trait, kind of a take it or leave it,” she says. “Now we have breeders who view it as a necessity trait.”

The older and younger ends of the age spectrum, along with part-timers and single-producer operations may benefit the most from introducing docility selection to their program. Even those who see no strong need for that focus may see the dollar impact when buyers compare animals.

“Producers need to continue being good stewards of this trait,” Northcutt says, “because genetics have an impact throughout the value chain.”

You may also like

Everything They Have

Progress is a necessity on the Guide Rock, Nebraska, ranch where Troy Anderson manages a commercial Angus herd, small grower yard, his 10-year-old son, and a testing environment. Troy’s approach includes respect for his livestock, people and land. For that, Anderson Cattle was honored with the CAB 2023 Commercial Commitment to Excellence Award.

Making It Better

Most sane folks don’t choose to go into business with Mother Nature. She’s a fickle and unpredictable partner. So, how did two people with zero agricultural background, no generational land, wealth or genetics carve a profitable partnership with her in Southwest Kansas? By focusing on progress and a desire to leave things better than they found them – which also earned them the CAB Sustainability Award.

A Drop of Hope, A Heap of Hard Work

For Manny and Corina Encinias’ family of nine, sustainability runs deep. They are stewards of a legacy, working the land dating back to 1777, when the first generation began herding sheep in the nearby Moriarty community. Today they focus on cows well suited to the harsh New Mexico desert, fostering community strength and creating opportunities for others to follow in their footsteps.