Every Issue Has Its Moment

And this is it for yield grade and red meat yield.

by Lindsay Graber Runft

April 2025

Pivotal moments happen when innovation meets progress.

In the early 1800s, there were untapped markets out East, so railroads were built—connecting cattle producers to opportunity. Ebbs and flows in cattle numbers and feedstuffs have been met with new technologies to improve feed efficiency and performance at the feedyard. And when consumer demand for beef tanked, the first National Beef Quality Audit was launched.

Over time, various beef industry issues have surfaced. Research and revolutions led to solutions. But what’s currently risen to the top in priority? Accuracy in yield grade assessment and the ever-present need for increased red meat yield.

It’s an important topic, one that all segments of cattle production and merchandising are leaning into. The goal is to produce as many pounds of high-quality beef, per carcass, as possible—and do it efficiently and sustainably.

A history lesson in grading

Based on metrics for confirmation and finish, quality grading began in 1927. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, interest began to build for yield measurement. By measuring several variables, meat scientists began work on calculating yield grade, an estimation of cutability.

Led by Charlie Murphy, a team of researchers settled on four variables to estimate the amount of boneless, closely trimmed cuts from the rib, loin, chuck and round – the makings of the beef carcass yield grade. The yield grade (YG) equation includes hot carcass weight (HCW), ribeye area (REA), backfat thickness (BF) and kidney, pelvic and heart fat (KPH).

The yield grade equation was indexed into a scale from one to five. Since June 1965, carcasses have been scored for yield grade, first by humans and today by camera technology.

Opportunities realized

It’s been 60 years since the first yield grades were assessed on the packing plant floor. And even longer since the yield grade equation was developed. Over the span of those six decades, market animal composition—alongside cattle feeding technologies and methods—have changed. Animal frame sizes were short and boxy, then frame scores skyrocketed, and cattle have now become more moderate in build. Current with today’s cattle cycle, average days-on-feed have extended, and carcass weights are reaching all-time highs.

It might be assumed that heavier carcass weights equate to increased pounds of beef. Dressing percent? Yes. But saleable beef? No.

Every issue has its moment. And this is it for yield grade and red meat yield.

Intertwined, yet not necessarily the same thing.

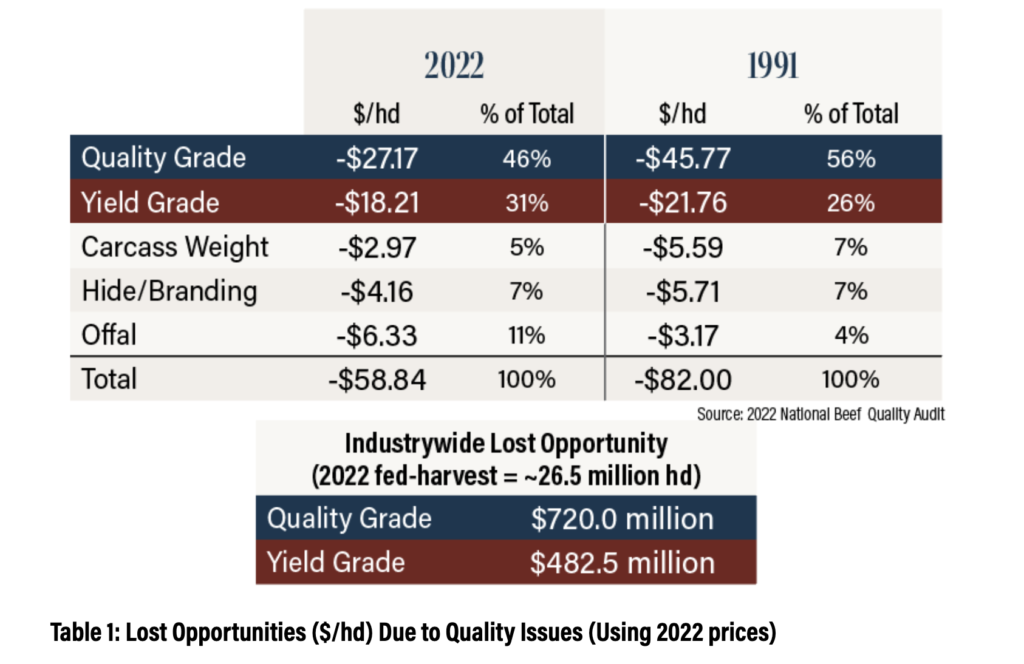

The first National Beef Quality Audit occurred in 1991, with the beef industry ranking its top five priorities for improvement. Since the first audit, yield and composition have consistently been identified as priorities, alongside palatability and eating experience, laddering up to increased producer profitability.

Where YG 1s and 2s get a premium, YG4s and 5s often receive a discount. On a 1000 lb. carcass, that could mean a $12-$200 dollar hit to profit. As explained by Dr. Ty Lawrence, professor of animal science at West Texas A&M University, during the 2025 Cattle Industry Convention’s (CIC) Cattlemen’s College, more than half the nation’s feeder cattle population falls into the YG3 category, while approximately 18 percent are YG4s and 5s.

“Producers are making decisions on individual animals—which bull to breed to which cow to maximize or optimize a certain trait,” says Blake Foraker, assistant professor at Texas Tech University’s Department of Animal and Food Sciences. “I think our industry has proven time again, pending what trait, we’ve moved more towards granular data (individual animal type) and that’s where we’re at with yield grade today.”

With quality directly tied to consumer demand for beef, it remains a high priority. But as the industry evolves, there is a growing relevance of yield alongside quality.

“With all the improvement that we’ve made in quality, it’s still the biggest lost opportunity for us,” says John Stika, CAB president. “But at the same time, because of the improvements we’ve made in quality, the relative scope of the opportunity between quality and yield grade is beginning to narrow.”

And it’s not just about profitability. The sustainability of current feeding practices and packing plant work come into play too.

“It’s the energy to put the fat on, cool the fat down, take the fat off of the carcass, and the energy to render it back to where we need it,” says Mark McCully, chief executive office at the American Angus Association. “If we were going to draw out on a whiteboard the ideal way to do this, that’s probably not where we’d end up.”

Average days on feed have extended to top end of 240 days at the feedyard. That’s 240 days of resources spent—from feedstuffs and water to labor—with return on investment in question.

Through changes in genetics and management, the opportunity exists to increase carcass weight, without putting on excess fat. Those “pounds of gold,” as Stika has coined them, would be high quality, saleable beef—through increased red meat yield.

It’s a significant, persistent topic. It’s no secret that the yield grade equation is due for an update, and the accuracy of it has been the subject of questions for several years.

“Sometimes our work in science has a lifespan, and we’ve got to be aware of how the market and industry evolve around us,” Stika says. “We’ve always got to be willing to circle back and reconfirm whether or not the sound results we found at that time are still relevant.”

A large percentage of cattle are traded on a formula and carcass merit basis, applying pressure to the need for a consistent and precise measurement. Lawrence noted that researchers can explain approximately 40 percent of the variation in red meat yield by yield grade. But it could be better.

Another opportunity. And one that extends to REA.

For decades, ranchers have used REA as a key indication of muscularity in cattle. Via ultrasound and camera-grading systems, it’s easy to get data back that can be used to improve genetic selection. With REA as the only tool, and its relation to yield grade calculations, cattlemen and women have homed in on that trait for red meat yield. But like yield grade, its measurement has come into question.

“The problem is we’ve given them (ranchers) only ribeye area, not true muscling,” Dale Woerner, Cargill Endowed Professor at Texas Tech University, says. “So when we single-trait select for ribeye area for muscling, even though it’s not related very well to muscling, we actually grow those relationships apart.”

Woerner notes that REA and red meat yield are only four percent related. And while it is still an important trait, it shouldn’t be the sole predictor of red meat yield.

“Ribeye area is the tool that we’ve largely put in the toolbox of breeders to improve red meat yield,” McCully says. “And it’s not directionally taking us the wrong way, but we have the opportunity to collect new phenotypes for genetic evaluation that would put new tools in breeders’ hands to truly make more advanced improvement.”

The beef industry recognizes the need to research red meat yield, and it’s poised to do so. Right alongside maintaining a .

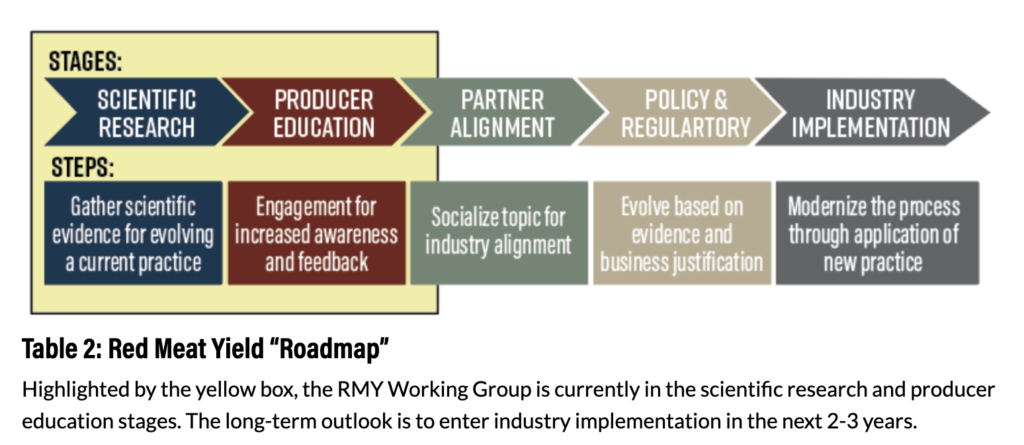

To answer the call for research, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) created the Red Meat Yield (RMY) Working Group. The NCBA RMY Working Group includes broad representation across industry stakeholders, with every segment of the beef supply chain weighing in—from cow-calf producers to the packing plant, and beyond with academia, government, technology expertise and merchandising/branded beef represented.

Current research priorities

With a roadmap to guide next steps, the RMY Working Group is moving forward to determine best practices through new technologies. Some technologies exist, though not yet practical for usage.

Via the RMY Working Group, key research has included how to define red meat yield by today’s standards, calculate red meat yield, and the processes to measure carcass composition. Through computed tomography (CT scanning), researchers can determine carcass composition, and it’s been deemed the “gold standard.” With the use of that x-ray technology, meat scientists can measure muscle, fat and bone at a high degree of accuracy.

One big challenge is incorporating it at the packing plant. The feasibility is low with chain speeds, alongside other logistical problems and safety issues.

But what it can do, is guide future research via the RMY Working Group. Using a “gold standard” like CT scanning provides opportunity to

Those advancements could guide development of practical plant and ranch-level technologies. The end game is a tool that can be used to accurately predict red meat yield and assess value of carcasses in live cattle—ultimately allowing for genetic selection for red meat yield.

At the table

Progress happens when people are at the table, engaged and committed to action. With a vested interest in the beef industry’s future, CAB is leaning in on conversations surrounding evolutions in meat science.

Quality has always been where CAB “hangs its hat,” but it’s not the only thing that keeps the brand relevant. A core priority for the brand—and an opportunity for Angus ranchers—is industry profitability. It gives producers a vehicle to put more dollars in their pocket, by targeting a brand favored by consumers.

On the flip side, producing excess fat equates to expensive pounds.

“We should be able to produce pounds of gold as efficiently as possible,” Stika says. “Right now we are producing pounds of gold, but with a lot of fat alongside it.”

Those “pounds of gold” are high-quality beef, and that quality attribute is important. Because of ranchers’ dedication to and focus on improving it, we’re currently enjoying the highest demand for beef in 30 years. There’s no going back on low quality beef; as a beef community, we cannot afford to improve red meat yield and go backwards on quality.

As we talk about this being an industry opportunity, it’s got to be good for everybody, meaning it can’t just benefit the packer,” Stika says. “It must ultimately produce dollars that come back to the feeder and the cow-calf producer—ultimately increasing the value of genetics that are able to hit the targets.”

Whereas the consumer’s not the driver, the industry is. As the topic continues to be socialized and research wheels put into motion, CAB remains committed to the push for establishing an accurate measurement and increased red meat yield—alongside production efficiency, sustainability and Angus ranchers’ bottom line.

Originally published in the April 2025 Angus Journal.

You may also like

Working in Balance

Cattlemen have a responsibility to look critically at their own herd, determine the areas that warrant improvement, and select animals accordingly. Stockmen bring immense value by objectively evaluating phenotypes, regardless of what the numbers say, and setting individual breeding objectives.

Healthier Soils and Stronger Herds

Effective land stewardship requires an understanding of how each decision affects forage growth, cattle performance and long-term stocking rates. When land is the foundation of the business, producers are more likely to invest time and resources into managing it intentionally.

Smitty’s Service on CAB Board

Lamb continues to find himself struck by just how far-reaching the Angus breed has become. The brand’s growing demand and rising prime carcasses left a strong impression. He hopes everyone recognizes the vital connection built between consumers and Angus producers. Humbled by the opportunity to serve, Lamb reflects on his time as chairman with gratitude.