The idea that worked

USPB earns CAB Progressive Partner honors

by Miranda Reiman

October 2021

To tell the U.S. Premium Beef, LLC (USBP) story today, is to tell one that changed the beef industry for the better.

There are numbers like 17 million head processed, with individual data collection on each one. More than $625 million in grid premiums back to the cattleman while establishing the model for grid marketing that brought the rest of the industry onboard to price cattle on individual merit.

“There were a tremendous number of individuals who, each with a collection of ideas, became a team,” says Tracy Thomas, USPB vice president of marketing. “And that team became very, very synergistic in result.”

But telling the story of USPB from the beginning starts with one word: Fear.

It was the mid-1990s; beef demand was tanking.

“Our product was bad and nobody wanted it. We were losing market share at a record rate,” says Mark Gardiner, Ashland, Kan., Angus breeder.

A “godfather” of the beef business, Michigan animal scientist Harlan Ritchie wrote his well-known, “Five years to meltdown,” article. At the aggressive speed with which demand was tailing off, it warned within five years beef would no longer be a viable protein. Some scoffed, some heeded Ritchie’s caution, and Gardiner asked his dad, Henry, “Could that really happen?”

The answer told his son there was no time to lose.

“Fear is a pretty powerful motivator. The fear factor was very, very high,” Thomas says.

Cattle feeders were having trouble with market access—they couldn’t even get their cattle sold some weeks. Each Monday they hoped the show list had enough “fancy” cattle to use as a bargaining tool to sell the remaining finished animals on inventory.

Commercial producers who invested more in good bulls and vaccinations found their cattle selling for the same price as those from ranchers who didn’t.

Gardiner and wife Eva had twin toddler boys at home, and a life’s dream that only ever included raising cattle where his great-grandfather had first made his start in a dugout. The need to survive was personal. He had to do something.

For their influence on the beef business, shifting toward quality and value-based marketing, USPB recently earned the Certified Angus Beef (CAB) 2021 Progressive Partner Award.

Lunches and late nights

Kansas State University may have made them fraternity brothers, but the cattle market situation united many early players as champions of the quality beef movement. Steve Hunt and Mark Gardiner swapped ideas over a Pizza Hut lunch buffet, and more and more alum joined their cause during the next few months.

Commercial cattleman Roger Giles, Giles Ranch at Ashland, Kan., had been trying to figure out a way to make his investments in genetics and management make sense.

“We really bought into it because at the time, we were losing a lot of money feeding cattle,” Giles says, noting the better cattle came with lower health cost and gained better but “you were just getting killed when you sold them.”

He was all in.

Near Scott City, Kan., cattle feeders gathered at hushed evening meetings, just to discuss the “what ifs” that included everything from building their own plant to hiring a czar to sell their fat cattle.

“I’ve said it before, but the success of a rain dance has a lot to do with the timing. The timing was just right, because even though we all thought we were educated going in, there was a big learning curve,” says Joe Morgan, Poky Feeders, one of the founding USPB members. His conference table was witness to many of the early discussions, not all of them tame.

“We all had opinions—we were all used to running our own companies,” Morgan says. “One night we all shook hands that we’re going to leave every night as friends, no matter how upset we got during the meeting. I think that was a real key.”

Competitors by day became allies by night.

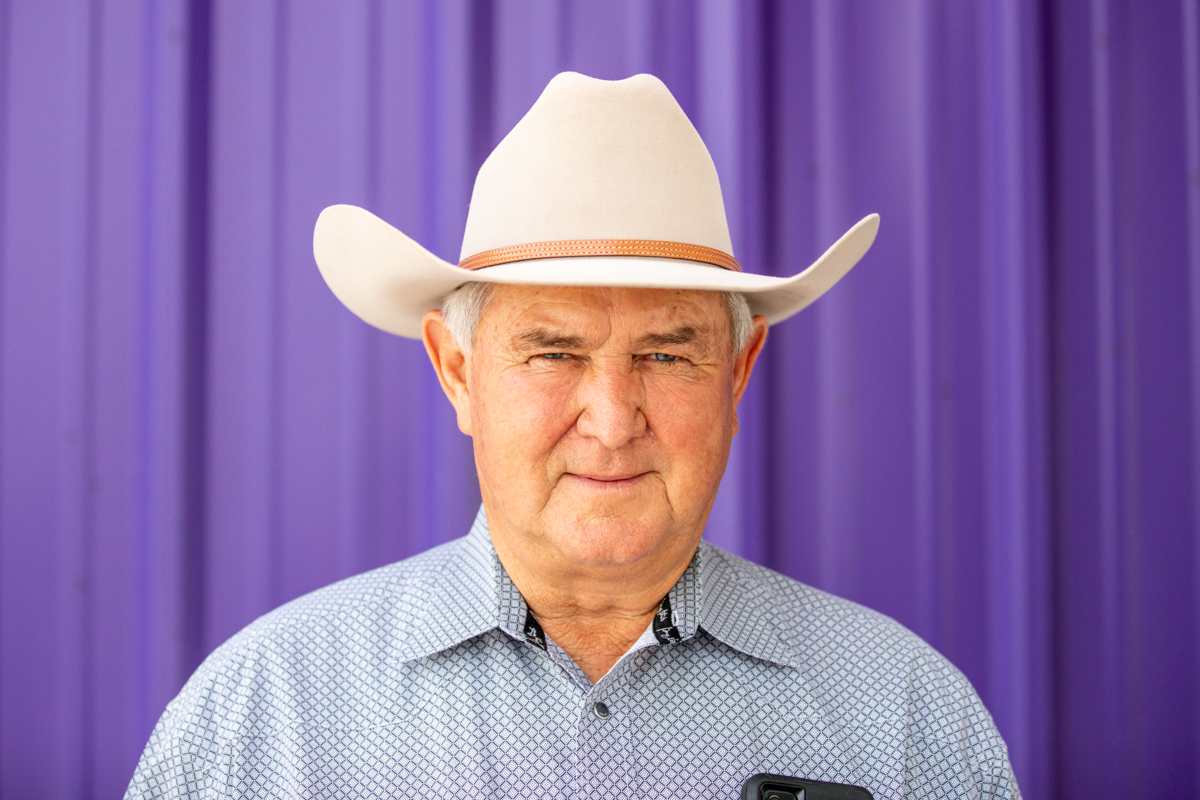

Mark Gardiner, Gardiner Angus Ranch

Tracy Thomas, USPB

Peddling blue sky

In late 1995, a formal group assembled and went out on what Gardiner refers to as the “Blue Sky Tour,” selling an idea. Sometimes it went well and sometimes they were run out of town, but soon enough, cattlemen from across the country were pledging support to the developing business model.

Common ground with Farmland Industries, an organization used to the cooperative model, led them to a letter of intent to purchase up to 50% of what was then Farmland National Beef Packing Company, LP (FNB). It was the fourth-largest beef processor in the U.S.

The USPB stock offering went live in October 1997, and by December the new company was buying up to 10,000 head of cattle a week from its producer members. Each share carried the “right and obligation to deliver one head to your processing plant,” Thomas says, and the minimum point of entry was 100 shares.

Roger Giles, Giles Angus Ranch

Joe Morgan, Poky Feeders

John Fairleigh, Fairleigh Feedyard

The reality of the risk

“Looking back, I don’t know if I could do it again,” Morgan says, noting many ventures came after and failed. “We were just so desperate, and young, and thought we could make it work. Actually it bothered me more after I got older, looking back at the risks we really took and the sacrifice we could have made.”

Bankers across the country tried to talk their cattlemen customers out of writing the check. John Fairleigh, Fairleigh Feedyard and fellow founding member, remembers the day he bought in.

“I was shaking. It was a very, very big investment, kind of rolling the dice and throwing it all in one basket,” he says. Today they still sell 100% of their cattle on the USPB grid.

Giles says it was a huge risk, but it felt like the only option.

“You had a bit of caution, but overall it’s one of these deals, it’s like we really don’t have a choice. We either have to move forward or we give up.”

Giles doesn’t come from stock that gives up.

Gardiner’s brother Greg says, “Everything I did have, I threw in the middle of the table and gambled that it would turn out.” It was a stretch, but now on the other side of that decision he wishes he would have dug deeper and put in even more. “As it has come to fruition,” he says, “it kept our business afloat.”

Growing pains

They may have celebrated when the deal went live, but the celebration didn’t last long before reality set in.

“We all thought when we started U.S. Premium Beef that our cattle were way better than our neighbors’ and for sure better than the industry,” Fairleigh says. They had confidence the newly established grid would be in their favor.

Across the nation, less than half of fed beef was grading Choice, and USPB soon realized its harvest ran lower still. Gardiner recalls their cattle makeup was $6 to $8 per hundredweight (cwt.) below the nation-wide average.

“So it changed the way we bought feeder cattle, who we bought cattle from and what type of cattle we bought,” Fairleigh says. “I think the industry has followed suit.”

For some feeders, it cost them their customers.

“Most people thought they had the best cattle, and a lot of them found out they didn’t,” Morgan says. “When you start knocking somebody’s farm-raised cattle, it’s like knocking their children. It was very difficult for us, the first few years, for people to accept that they needed to make genetic change.”

An initial grace period with FNB guaranteed them at least the market average each week, and with individual carcass data in hand and a grid target to hit, cattlemen got to work.

Change, one head at a time

“If truly higher quality cattle were what the market was looking for, if we could tap into and identify the genetics that would move the dial, then we had the vehicles to produce those types of cattle,” says Greg Gardiner. “Once you have the vehicle to go, then it’s pedal to the metal and foot-feed to the floor because you can do it time and time again. It’s a highly repeatable process.”

It’s been more than two decades since the USPB grid was introduced, and now every major packer has marketing options to sell cattle on individual carcass merit. In 1997 some 40% of all USPB cattle graded Choice and fewer than 10% qualified for CAB. Last year, USPB cattle averaged 89% Choice and Prime—a record high—and annual CAB percentage have averaged 28% the past five years, with an additional 3% CAB Prime.

“Consumer demand is the ultimate driver for what we produce,” Fairleigh says, noting insight from being coupled with a packer. “We had seamless information to guide our guesses to as what consumers wanted.”

The cattle changed from the “rainbow coalition,” Gardiner says, to a more solid set of uniform cattle. The Angus breed led the improvement.

Return on investment

“We have created a tremendous product now and got consumer confidence, consumer acceptability and we’ve got the demand now,” Morgan says.

USPB members have collectively earned $2.1 billion in payments, grid premiums and cash distributions from ownership in processing.

It worked, and it continues to work.

Today, USPB has more than 2,900 members and associates in 38 different states, and an approximate 15% ownership interest in National Beef Packing Company, LLC. The advantage of remaining vested in the packing sector was as evident in 2020 as it was at the start. COVID-19 made its mark as it did for everyone, but USPB members had an option based on an allocation system.

“They were able to get their finished cattle into the processing plant when it was difficult to almost impossible in other places,” Thomas says.

The USPB mission includes increasing both the quality of beef and long-term profitability for cattle producers, and Gardiner says they’re as focused on that as ever.

“We all love this business, but every cow is connected to a human. So, if we make sure the humans can be prosperous and survive, that’s what sustainability is,” he says. “That is the opportunity that USPB gave our family and thousands more all across the United States.”

Beef demand is up more than 30% on the year. That’s motivation, Gardiner says.

“We’ve only just begun.”

Originally published in the Angus Journal and Angus Beef Bulletin.

You may also like

Showing Up, Every Day

Thirty-five thousand cattle may fill these pens, but it’s the Gabel family who set the tone for each day. Steve and Audrey persistently create a people-first culture, echoed by their son Case and daughter Christie, who work alongside them in the yard office. The Gabel’s drive to effectively hit the high-quality beef target earned Magnum Feedyard the CAB 2023 Feedyard Commitment to Excellence award.

From the Ground Up

Benoit Angus Ranch, a seedstock operation that markets more than 150 bulls annually, is a multi-generation family business with sons Doug and Chad now heavily involved. Focused on serving the commercial cattleman, the Benoits built a reputation for high-quality cattle that perform on the ranch, in the feedyard and on the rail. With always-improving cattle to support that renown, and the will to back it up, Benoit Angus Ranch earned the CAB 2023 Seedstock Commitment to Excellence Award.

Future Focused Business

Pilot partners in CAB’s Ranch to Table program, these North Dakota ranch families took some of the market volatility into their own hands in April 2022. Their leap of faith provides high-quality beef options for their communities and diversifies their income. Now they sell their finished cattle, as well as those of their customers, through Dakota Angus, a direct-to-consumer beef business.